Push to Scale Back Sentencing Laws Gains

Momentum

By JENNIFER STEINHAUER JULY 28, 2015

WASHINGTON — For several years, a handful of lawmakers in Congress have tried to scale back tough sentencing laws that have bloated federal prisons and the cost of running them. But broad-based political will to change those laws remained elusive.

Now, with a push from President Obama, and perhaps even more significantly a nod from Speaker John A. Boehner, Congress seems poised to revise four decades of federal policy that greatly expanded the number of Americans — to roughly 750 per 100,000 — now incarcerated, by far the highest of any Western nation.

Senator Charles E. Grassley, Republican of Iowa and chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee who has long resisted changes to federal sentencing laws, said he expected to have a bipartisan bill ready before the August recess.

“It will be a bill that can have broad conservative support,” said Mr. Grassley, who as recently as this year praised the virtues of mandatory minimums on the Senate floor.

Even in a Congress riven by partisanship, the priorities of libertarian-leaning Republicans and left-leaning Democrats have come together, led by the example of several states that have adopted similar policies to reduce their prison costs.

As senators work to meld several proposals into one bill, one important change would be to expand the so-called safety-valve provisions that give

discretion to sentence low-level drug offenders to less time in prison than the required mandatory minimum term if they meet certain requirements.

Another would allow lower-risk prisoners to participate in recidivism programs to earn up to a 25 percent reduction of their sentence. Lawmakers would also like to create more alternatives for low-level drug offenders. Nearly half of all current federal prisoners are serving sentences for drug crimes.

Republicans including the highly conservative Senator Mike Lee of Utah and liberal Democrats like Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey have become unlikely allies, citing as the impetus for change federal overreach, ballooning costs and lives they have seen erode behind bars that could have been better served in drug rehabilitation or other programs.

“The caricature of the conservative view on this is that we are in this to reduce costs in the prison system,” said Mr. Lee, a former federal prosecutor who has been working for months with Senator Richard J. Durbin, Democrat of Illinois, who has spent much of his nearly two-decade Senate career trying to overhaul sentences.

“But the biggest issue involves the human costs.”

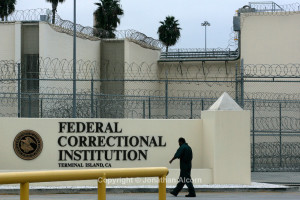

Of the 2.2 million men and women behind bars, only about 207,600 are in the federal system, according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons. But because the federal system has grown at the fastest rate of any in the country, many on the left and the right say they believe it exemplifies the excesses of America’s punitive turn.

“If we can show leadership at the federal level,” Mr. Durbin said, “I think it will encourage other states to open this issue up for debate. The notion that we can create a bipartisan force for this really has value.”

Former President Bill Clinton focused on the issue last week in a speech to the N.A.A.C.P. when he disavowed part of a crime bill that had been considered a signature domestic policy achievement. Mr. Clinton said the legislation went too far and sent minor criminals to prison “for way too long.”

The movement to make these changes comes after years of resistance from the chairmen of the judiciary committees who are now being reluctantly pulled along by other members to move on bills that would overhaul the entire federal prison system, including measures that would change sentencing, a point of dispute for decades.

“I’ve long believed there needed to be reform of our criminal justice system,” said Mr. Boehner, endorsing a House bill that would change the system. “We’ve got a lot of people in prison, frankly, that don’t really in my view need to be there. It’s expensive to house. Some of these people are in there for what I’ll call flimsy reasons.”

The dynamic is similar to the fight this year over changes to the Patriot Act when younger, more libertarian members — again supported by Mr. Boehner and Mr. Obama — worked with Democrats to change the law and eventually even won over a reluctant Mr. Grassley.

The rise in prisoners has been a direct outgrowth of changes in sentencing laws.

In the middle of the century, the United States was on par with other Western nations with incarceration rates hovering roughly around 170 people per 100,000, said Sharon Dolovich, a law professor and sentencing expert at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Indeterminate sentencing — giving judges great latitude in how they punish people — was standard for many crimes, although there was concern that surfaced in the 1970s among experts that this discretion often led to discriminatory sentencing disparities.

During the 1970s and ‘80s, an increase in crime over all coupled with the socalled war on drugs led to expanded sentences, supported by Democrats and Republicans. The number of those going to prison and the length of time spent behind bars by offenders skyrocketed after 1986, when Congress established mandatory minimum drug sentences.

Now, the debate over how to reverse this breaks down among those who favor broad changes to sentences, including the reduction of mandatory minimum sentences, those who want to address early release and services behind bars, and those who favor a blended approach.

In the House, there is a parallel bipartisan effort afoot, set off in part by the notion, Republicans said, that there has been an “overcriminalization” of certain conduct that they perceive as another form of regulatory growth. For instance, they cite the case of a man who spent six years in a federal prison for importing Honduran lobsters that were packed in plastic — as opposed to cardboard — boxes.

Representatives Jim Sensenbrenner, Republican of Wisconsin, and Robert C. Scott, Democrat of Virginia, are sponsoring a bill that would change sentencing on the front end and also change the federal probation system. Another provision would give certain qualifying prisoners the opportunity to get 33 percent off their sentences.

Proponents of changes to sentencing laws are now staring at what they say is the first real open window in decades to make meaningful change, and they are fearful that lawmakers may tinker around the edges of a prison overhaul — allowing people to leave jail early for good behavior and increasing services for juveniles — while leaving the thorny sentencing issue to fester.

“The current conversation was prompted by a realization that incarceration is very high and the return on investment is very low,” Ms. Dolovich said. “With that realization has come a shift that has gone from a financial imperative to a moral imperative. But it seems like there is a danger that all of this seeming interest around the need for criminal justice reform may not actually end up touching the most vital aspects of the problem.”